Development: Issues Across the Lifespan

- Introduction: Some Terms | What Makes People Gay?

- Identity

- Childhood & Adolescence

- Coming Out

- Bisexuality

- Couples: Lesbians | Gay Men

- Parenting

- Aging

Goal

At the completion of this module, the participant will be able to identify developmental issues specific to LGBT people across the lifespan.

Objectives

The participant should be able to demonstrate:

- familiarity with coming out as a developmental process specific to LGBT people

- knowledge of issues specific to gender-atypical children, LGBT youth, adults, and older adults

- familiarity with issues relating to same-sex couples

Pre-Test

- Bisexuals are people who date men and women simultaneously.

- True

- False

- Children who present with gender atypical behavior always become

transgendered adults.

- True

- False

- Coming out as LGBT is a process that takes place between:

- Ages 10-15

- Ages 16-20

- Ages 21-25

- Ages 26-30

- No particular ages

- Older LGBT adults:

- do not exist currently because people did not start coming out before the 1980's

- may have different adjustment issues currently than LGBT adults who turn 65 ten years from now

- stop having sex at ages later than heterosexual adults

- often revert to heterosexuality in late life due to the lack of same-sex partners

Introduction

Click to enlarge.

Cartoon courtesy of Alison Bechdel. Used with permission.

Some Terms

- Gender identity

- How one label’s one’s gender, whether male, female, transgender, or another identity (e.g., genderqueer).

- Gender minority

- Having a minority gender identity: transgender, genderqueer.

- Sexual orientation

- Whether someone is primarily attracted to people of the same sex (homosexual), the opposite sex (heterosexual) or both (bisexual).

- Sexual identity

- How one consciously labels one's sexuality, whether gay, straight, bisexual, or another identity label (e.g., queer, bi-curious).

- Sexual behavior

- A person may engage in a variety of sexual behaviors with males and/or females or no sexual behaviors at all, yet self-define her/his sexual orientation on another basis. Therefore, current research in areas such as HIV or sexually-transmitted infections where behavior is more relevant than identity will use descriptors such as MSM, men who have sex with men.

- Sexual minority

- Having a minority sexual identity: gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer.

What Makes People Gay?

We do not know why some people are gay any more than we know why other people are straight. Earlier psychoanalytic case reports that proposed pathological family dynamics have long since been discredited. More recent biological studies reporting findings such as variance in the size of certain hypothalamic nuclei or genetic linkage differences have suffered from methodologic limitations and lack of replication. At this point, most experts agree that the origins of sexual orientation are likely multifactorial and require further research. Although some combination of biological and environmental factors likely influence sexual orientation development, many LGBT people describe feeling "born that way" and view their sexual identities as a stable aspect of their essential selves.

Identity

Sexuality and sexual identities can be diverse and complex. Kinsey (1948, 1953) attempted to describe this diversity with the development of the Kinsey Scale. The Scale describes sexual attraction from 0 (totally heterosexual) to 6 (totally homosexual). Refinements of the Kinsey scale add other dimensions of sexuality (Klein et. al., 1985) and recognize that people not only fall between the 0 and 6 poles on the attraction continuum, but can have different ratings with respect to sexual attraction, with whom they fall in love, and sexual behavior.

Sexual identity, or how a person labels their sexuality, adds yet another dimension. A person with bisexual behavior (having sexual relations with both men and women) may self-identify as bisexual, gay, or straight. For example, a married man who does not feel attracted to women and has sexual experiences with men may have a homosexual sexual attraction but may nevertheless identify as "straight".

As acknowledging homosexual feelings and behavior often leads to stigma and discrimination, adopting a gay or bisexual identity usually means that a person has strong and predominant same-sex attraction. Still, some people, perhaps women more than men, have adopted a myriad of terms to describe differing shades of identity: gay, lesbian, bisexual, bi-dyke, and queer, to name a few.

Gender identity, one’s sense of being male, female, or transgender, can also be diverse and complex. Sexual identity and gender identity are separate things, so someone with a transgender or gender minority identity can have a sexual identity as gay/lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual, or asexual. Like sexual identity, we don’t know what causes someone to have one or another gender identity. Biological theories from prenatal hormones to genetic factors have been proposed, but the research is inconclusive at this point. See section below and transgender module.

Childhood & Adolescence

Gender Identity Development & Gender Atypicality

Gays and lesbians largely go through

similar developmental phases as their heterosexual counterparts. By age

2 or 3 most children most develop a stable gender identity, that

is, a sense of being a boy or a girl. Gender role, that is, one's

outward presentation and behavior as typically male or female,

continues to develop during preschool years and is actively regulated

by family members as well as peers. In retrospective studies, two main

features emerge in the early lives of gays and lesbians. Many adults

who identify as gay or lesbian recall feeling different from their

peers, sometimes for vaguely felt reasons. Often, however, this is

because of gender "atypical" or "nonconforming" behavior. This finding

may be partly a result of recall bias and the greater willingness of

gay and lesbian adults to acknowledge gender atypical behavior than

their heterosexual counterparts. While some gay adolescents, especially

males, report that they "always knew" that they were gay, they may be

conflating gender atypical behavior and same-sex affections in

childhood with homoerotic orientation.

Gays and lesbians largely go through

similar developmental phases as their heterosexual counterparts. By age

2 or 3 most children most develop a stable gender identity, that

is, a sense of being a boy or a girl. Gender role, that is, one's

outward presentation and behavior as typically male or female,

continues to develop during preschool years and is actively regulated

by family members as well as peers. In retrospective studies, two main

features emerge in the early lives of gays and lesbians. Many adults

who identify as gay or lesbian recall feeling different from their

peers, sometimes for vaguely felt reasons. Often, however, this is

because of gender "atypical" or "nonconforming" behavior. This finding

may be partly a result of recall bias and the greater willingness of

gay and lesbian adults to acknowledge gender atypical behavior than

their heterosexual counterparts. While some gay adolescents, especially

males, report that they "always knew" that they were gay, they may be

conflating gender atypical behavior and same-sex affections in

childhood with homoerotic orientation.

As many as two-thirds of adult gay men and women recall some gender atypical behaviors or preferences as children (Bailey & Zucker 1995). Clinicians are most likely to be confronted with issues of sexual orientation in cases of preschool and elementary school children with notably gender atypical behavior. For example, the tomboy girl who prefers boys' toys, games, hairstyles, and clothing and male playmates; she opts for male-typical roles in fantasy play. In rarer cases, she may insist that she is a boy or that she will turn into a boy with a penis later in life. Given the greater social acceptance of athletic behavior and masculine dress among girls in America, tomboys tend to have fewer problems in social adaptation than gender atypical boys. The latter usually have histories of cross-dressing in their sister's or mother's clothes, or fashioning dresses from towels or linens, favoring the performance of female musical roles, playing with girls' games and toys, and avoiding male peers and sports. Less commonly these boys insist they are girls or that their penis will be transformed when they grow up. Effeminate boys typically face much greater hostility than tomboys from their family, peers, teachers, and society.

The one prospective, longitudinal study of boys with significant gender atypical behavior ("sissy boys") found that 75 percent of these boys reported homosexual orientation as adolescents and young adults (Green 1987). Only one declared himself to be transsexual in adolescence. These subjects are not necessarily representative of all boys (let alone girls) who will grow up to be homosexual adults.

It is clear that gender atypical children face varying degrees of hostility and antigay bias from their families, peers, and even some mental health professionals. This hostility takes the form of marginalization, teasing, insults, assaults, and sexual violence. These in turn lead to feelings of shame, anxiety, depression, and poor self-esteem in the affected child. Some may actively and self-consciously struggle to alter their behavior to conform to peer expectations, cultural norms, and religious values. This can lead to a deeply ingrained internalized homophobia manifested as profound self-hatred, or externalized as anti-gay attitudes and aggression in adolescence and young adulthood. This aggressive suppression of this forbidden part of themselves can lead in later life to desperate attempts at heterosexual relationships, marriage and child rearing, while maintaining a secret life of homosexual activity.

The presence of gender atypicality or variance does not necessarily imply transgender identity. The few studies done indicate that relatively few boys with gender variance become transgender adults and most become gay adults. Parents with a gender variant child can be encouraged to help their child feel secure about their gender identity while minimizing ostracism and isolation. Child psychiatrists can provide treatment for any resulting distress or behavioral disorders and help parents discuss what it may be like to have a gay or lesbian child (Perrin 2004).

Adolescence

Sexual exploration and experimentation are common in adolescence. Many

heterosexual youth have sexual experiences with persons of the same

sex, and many homosexual youth with persons of the opposite sex. For

straight youth, this may represent curiosity and experimentation, while

lesbian and gay youth may be experiencing pressure to conform to

majority behavior.

Sexual exploration and experimentation are common in adolescence. Many

heterosexual youth have sexual experiences with persons of the same

sex, and many homosexual youth with persons of the opposite sex. For

straight youth, this may represent curiosity and experimentation, while

lesbian and gay youth may be experiencing pressure to conform to

majority behavior.

Adolescent development in LGB youth is often conceptualized using stage models that include phases of identity development such as awareness of difference, confusion about difference, decision and action (or indecision and inaction), acceptance, pride, and integration. However, these developmental stages have often been based on retrospective accounts of adults rather than prospective studies. Stage conceptions of sexual orientation development may not fully capture the messiness of real life with its overlaps, missing steps, and stages occurring out of order. Nonetheless, studies of LGBT young adults show that most recognized their sexual orientation during early adolescence, with awareness of same-sex erotic attraction usually predating puberty (Cohler 2000). [See also the Identity and Coming Out sections]

Coming out may be different for today's LGBT youth than it was for past generations. For some LGBT youth, expectations of stigma may be absent, and some aspects of LGBT life may even be considered "cool." Many adolescents with same-sex attractions do not identify as LGBT or have same sex-behaviors while adolescents, and some may consider labels such as "gay" or "lesbian" too constraining, calling themselves "queer" or rejecting all labels. Nonetheless, studies of LGBT young adults show that most recognized their sexual orientation during early adolescence, with awareness of same-sex erotic attraction usually predating puberty.

Stress Factors Influencing LGBT Adolescent Development

LGBT adolescents have the same basic needs as other youth: development of self-esteem, identity, and intimacy; social and emotional well-being; and physical health. LGBT adolescents may be especially vulnerable to not having their basic needs met. They may feel different from their peers, and unsure how their friends and family will react to their sexual orientation. They often lack other outlets for exploring their sexual identity, such as talking to mentors or same-sex dating. LGBT adolescents are subject to high rates of physical and verbal abuse, being forced out of their homes, and sexual assault (D'Augelli, AR 1995). Although most LGBT youth show remarkable resilience, these factors combined with stigma may be related to higher rates found in LGBT adolescents of dropping out of school, using tobacco, alcohol or drugs, suicide attempts, depression, and HIV disease (Frankowski 2004).

Physicians and LGBT Adolescents

Physicians, especially pediatricians and child psychiatrists, have an important role to play in addressing the development concerns of LGBT adolescents. It is essential that they strive to be open and inclusive in their interviewing and responses to questions from patients. For instance, rather than just asking whether a young girl has a boyfriend, she can be asked whether she has ever had a romantic relationship with a boy or girl . It is important to take a history about multiple aspects of sexual identity, including sexual attraction, self-labeling, and sexual behaviors. Confidentiality is essential, both to encourage openness and also because many LGBT youth have home environments that might become dangerous if their sexual identity is revealed. Clinicians should incorporate in their treatment of LGBT patients questions about available supports, HIV risk factors, physical and sexual abuse, drug and alcohol use, and suicidality. Referrals to psychotherapy should be considered to help teens clarify and become more comfortable with their sexual orientation and adjust to resulting issues and conflicts. Physicians can make referrals to LGBT resources such as gay-straight alliances at school (www.glsen.org) or The National Coalition for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Youth (www.outproud.org). Parent education is be essential, with the permission of the LGBT adolescent, and resources such as PFLAG (www.pflag.org) are available.

Coming Out

Click to enlarge.

Cartoon courtesy of Camper. Used with permission.

Coming out is the process of becoming aware of and acknowledging one’s own gay identity (coming out to oneself), and disclosing that identity to others (coming out to others). It is a developmental process unique to gay people. The concepts of coming out and gay identities are relatively new ones (see History module). The first sociological conceptualization of "coming out" was by Barry Dank (1971) who identified two critical steps: 1. being in a social context with or knowledge of homosexually identified people, 2. placing oneself in a new, destigmatized cognitive category of homosexuality.

Coming out to oneself

Awareness and development of a gay, lesbian, or bisexual (GLB) identity is not a single event, but a process, usually a lifelong process that parallels one’s development as a person. Coming out to oneself encompasses events such as awareness of a first same-sex attraction or crush, first same-sex kiss, feelings of being “different” from peers as a child or adolescent, self-questioning (“Am I gay?”), the first experience of going to a social event (e.g., a gay dance a gay bar, or a gay pride parade), self-labeling (“I am gay”), and many other events in a person’s life.

Coming out often starts in young adulthood, but can begin at any age or stage of life. Acknowledging, acting on, and integrating same-sex feelings into one’s identity can be an exhilarating and terrifying process. Coming out can be accompanied by mood swings and impulsivity, much like a second adolescence, and might lead to an erroneous diagnosis of borderline personality disorder by an uninformed clinician. Cass (1979, 1984) has described stages of coming out: Identity Confusion, Comparison, Tolerance, Acceptance, Pride, and Synthesis. While this provides some helpful framework, it must be noted that the process of coming out is often not linear, and individual gay people may not fit neatly into such models.

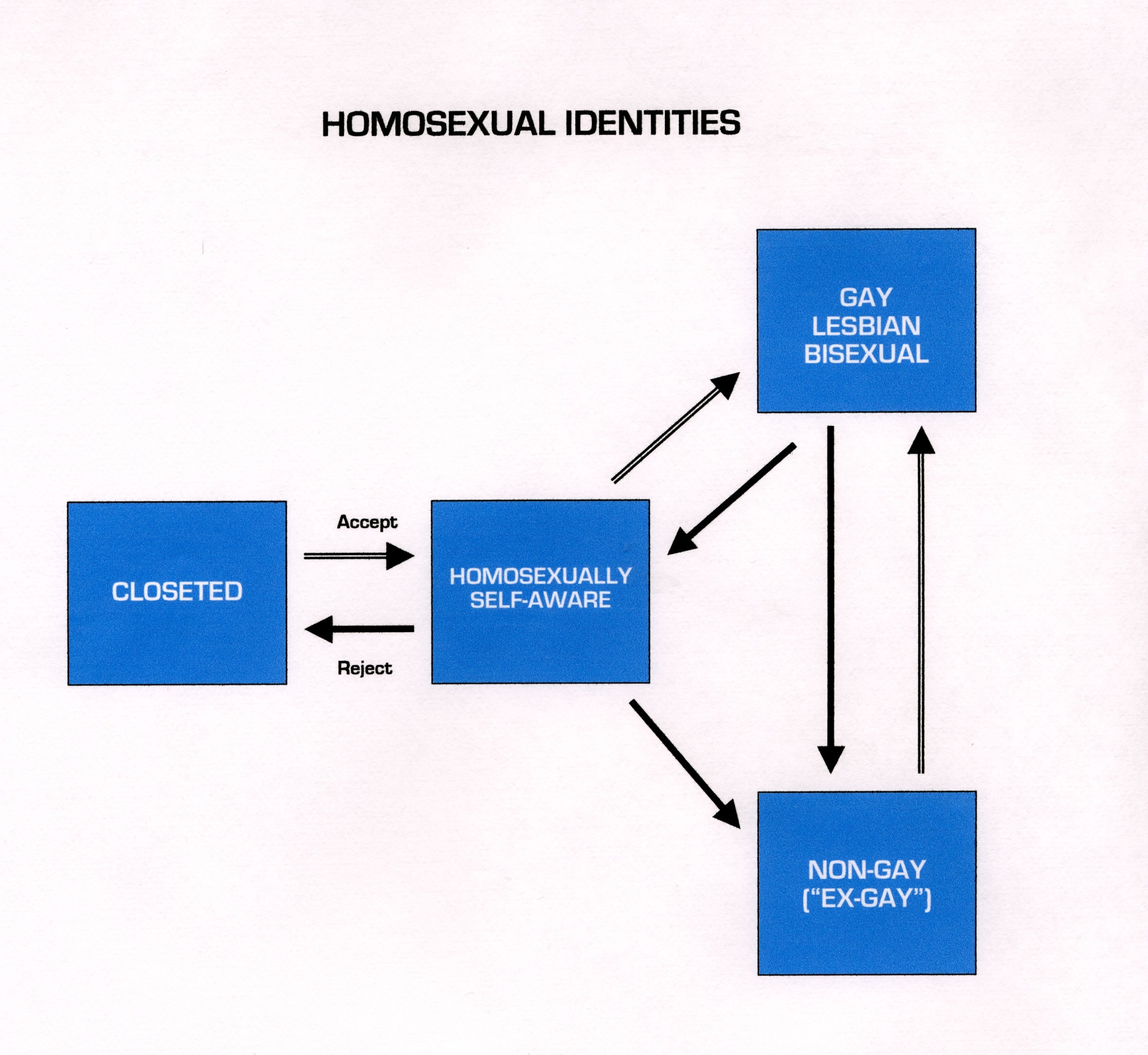

Not every person who becomes aware of same-sex attractions or desire ends up identifying as GLB. The person may accept or reject such feelings, and accordingly adopt a GLB identity or not. Over time, a person may become more or less accepting of his or her homosexual feelings and his or her sense of identity may shift.

A well-intentioned therapist treating a patient who is struggling with whether he or she is gay or lesbian may be tempted to quickly push a resolution. Comments such as, “You just have to accept that you’re gay,” or, “It’s really OK to be a lesbian” may be well-meaning, but are generally not helpful to the person in the midst of an internal conflict, and may even drive the person from treatment. It is also not uncommon for an adolescent or adult questioning his or her sexuality to ask the therapist, "Do you think I’m gay?" Again, rendering an opinion on how the therapist thinks the patient will (or should) work out his or her identity is generally not a helpful intervention. (See also the Psychotherapy module)

From Drescher (2004)

GLB people have internalized societal views of homosexuality (internalized homophobia, heterosexism), and often retain biased thinking and stereotypes about gay people (and by extension, themselves) even after they have apparently become comfortable with their identity. New situations and relationships can bring out these retained views, sometimes precipitating an identity crisis but also allowing for the possibility of further growth and maturity. Drescher (1998) describes a gay male patient who came into treatment after his ten-year relationship had ended. The patient was a middle-aged man who had long felt comfortable with his gay identity. Yet when the relationship ended, he had the thought that it was because “gay relationships can’t last.” The end of this relationship had called into question any future relationships, and indeed his whole identity. He felt paralyzed and unable to do the practical things needed to move on from the relationship. When he became aware of how his internalized homophobia emerged around the breakup, the patient was able to sell the house he and his ex-partner had owned together and to move forward

It has been generally believed that women come out to themselves at later ages then men, although the early literature did not support this (Barber 2000). More recent literature has shown that gender differences may exist, although not as simplistically as predicted. Savin-Williams & Diamond (2000) found in a group of sexual minority youth that men and women became aware of same-sex attraction at about the same age. Men were more likely to follow a "sex first" trajectory of having a sexual experience with another man and then self-labeling as gay. Women were more likely to follow a “label first” process of identifying as gay and then having a sexual experience with another woman. Some gender differences in coming out may be attributable to lesbian invisibility. Other potential factors are societal encouragement of men to express and women to suppress their sexual feelings, and differences in male and female sexuality in general. Additionally, there is known to be greater societal condemnation of cross-gender behavior in boys than girls, so that boys with cross-gender interests might be confronted by their difference at an earlier age than girls.

After coming out, sexual identity may still evolve over the lifespan. Diamond (2008) studied lesbians and bisexual women over time and found that some women, rather than becoming more certain in their sexual identity and behavior over time, become fluid, bisexual, and less likely to identify with a label such as lesbian. Diamond found that even some self-identified lesbians had relationships with men after coming out as lesbian. Men are assumed to not follow such trajectories, although there has not been a comparable longitudinal study on men.

Just as with LGB people, transgender people go through a process of self-awareness. This process may start in childhood, adolescence, or later. Transgender awareness is complicated by the need to make decisions about whether to physically transition through hormones and surgery. For a child expressing a transgender identity to parents and other adults, whether to medically intervene is an issue of some controversy. (See also Transgender module.)

Coming out to others

Since society assumes everyone is heterosexual (heterosexism), and since gay people do not have lavender skin or other obvious identifying characteristics, coming out to others is also a lifelong process. Everyday situations, from the critically important to the mundane, offer a gay person the decision of whether or not to disclose his or her identity. Becoming a parent, moving to a new town, changing jobs and other major life changes can open up a whole new sphere of people about whom a gay person will have to make this decision.

Clinical Examples

Raphael, a gay man, is at the checkout of a supermarket, buying among other items a bouquet of flowers for his partner. The woman at the register remarks, “Your wife is so lucky to have you!” Raphael may choose to challenge the checkout person’s assumptions and come out to her (“Actually I’m buying these for my partner Steve”) or may say nothing. The decision may hinge on what sort of day he’s had, his level of fatigue, how rushed he is, how safe a disclosure of a male partner might be in his town, and other factors.

Pamela, a lesbian who has a three-year old child with her partner is alone registering the child for admission to a daycare center. The center’s director has her fill out a form, which has a space for “mother” and “father.” Here the decision has greater consequences, in that if Pamela chooses not to put her partner’s name on the form, her partner will not be able to pick up the child or respond to the child in an emergency. On the other hand, Pamela may fear that the daycare will not accept her child for admission if the director knows she has lesbian parents, or that staff at the daycare will treat her child differently. These factors may be more or less important depending on the area in which they live, the scarcity of daycare slots, Pamela’s and her partner’s role in taking care of their child, and other issues.

Bisexuality

Although the dominant cultural paradigm of sexuality splits people into two groups, homosexual and heterosexual, research on human sexuality indicates that a substantial percentage of the population feels sexual attraction to both men and women. The term "bisexual" is used (1) as an adjective to describe sexual attraction to and behavior with both sexes and (2) as a noun to label individuals who have a bisexual sexual orientation. Bisexual people are not necessarily (and generally are not) attracted equally to men and women. The percentage of the population that feels sexual attraction to both men and women is larger than the percentage of the population that has sexual experiences with both sexes, which in turn is larger than the group that identifies as bisexual. For example, a heterosexually-married man who has sex with men is behaviorally bisexual, but may identify as straight (see "down low").

Some people may view themselves as bisexual during a transitional period when they are coming out, while others may maintain a lifelong bisexual identity. Those who do identify as bisexual over time sometimes face prejudice from members of the gay community who may assume that they are uncomfortable with coming out as gay or lesbian. Gay men and lesbians may accuse bisexuals of enjoying heterosexual privilege, particularly if they are heterosexually partnered or married. However, heterosexually-partnered bisexuals face increased invisibility and isolation as people around them assume that they are straight. They may face bias from straight people who sometimes wrongly assume that being bisexual means that the person needs to have male and female partners simultaneously. Because bisexuals may not feel fully accepted by either the gay or the straight community, they may seek out other bisexuals for support (biresource.net, www.binetusa.org).

Couples

All couples face a host of challenges establishing and maintaining their relationship. They bring their own developmental history and capacity for intimacy. There are both internal and external factors that affect the stability of the relationship. What follows are some of the specific issues that lesbian and gay male couples may face.

The Lesbian Couple

Many issues lesbian couples face are the same as for heterosexual couples, but there are also specific issues that arise for lesbian couples that do not arise in heterosexual couples. For example, each partner's degree of comfort with being openly lesbian may vary and conflicts may arise around issues of disclosure. Internalized, unexamined homophobia may influence each partner's level of confidence in the viability of the relationship. In some cases, entering a lesbian relationship may initiate a woman's coming out to herself, to family and to friends. Others may rationalize the relationship as a "special circumstance" and think of themselves as a "straight woman in a gay relationship."

The degree of cohesion and relatedness has been found to be higher in lesbian couples than in gay male and heterosexual couples (Zacks 1988). For some, this may lead to a phenomenon termed "fusion," conceptualized as a blurring of boundaries to the point of extreme emotional closeness (Spitalnick and Macnair 2005). This can present as a problem when the partners have difficulty developing autonomous identities.

A lesbian couple's development may be complicated by a lack of internalized role models for their relationship (Spitalnick and Macnair 2005). Couples may misinterpret difficulties in a relationship as being secondary to their sexual orientation rather than as being generic relationship difficulties. Conventional wisdom, not to mention gender stereotypes, may presume that two women have a more egalitarian relationship when it comes to sharing tasks and household roles. While every couple needs to figure out issues such as division of labor in the household and finances, the lack of expectations of roles and tasks in a two-woman relationship may lead to anxiety.

Historically, lesbian communities often divided into two gender categories: butch and femme. The butch was more stereotypically masculine and the femme stereotypically feminine in terms of appearance, social role, and sexual roles. Such strict roles are much less common today than a generation ago, but in some couples and communities, they still exist. Some couples play with these roles with an element of tongue in cheek (e.g. "butch in the streets, femme in the sheets," referring to oneself as a "butchy femme" or "soft butch"). These labels may sometimes cross over into transgender identities, e.g. "bois" (pronounced boyz, very butch lesbians, some of whom may consider themselves to be very masculinized and some of whom may consider themselves to be male), "tranny fags." [See Transgender module.]

Lack of validation from family, friends, coworkers, and legal and religious institutions can be painful, and lesbian couples may need to create alternative networks for social support. For families of origin, incorporation of a family member as part of a lesbian couple is another step in the coming out process; it becomes more difficult for families to evade disclosure to their friends or community if their family member is part of a couple. The degree of a couple's acceptance by families is often disparate and each member of the couple may not feel comfortable with the attitudes of her partner's family.

In early studies (Kurdek 1988, Kurdek 1989), almost 100% of lesbian couples reported sexual exclusivity. A couple's frequency of sexual interaction was reported to decrease after a year (Blumstein and Schwartz 1983). Historically, within lesbian communities, much was made of a phenomenon known as "lesbian bed death" (Hall 1996). This described a sharp decrease in a couple's sexual activity following the initial excitement of starting a relationship. Potential explanations for this phenomenon include: lower sex drive among women, a culturally derived reluctance of women to initiate sex, and intimacy in other aspects of the relationship leading to a "merging" that contributes to lessened sexual excitement (Spitalnick and McNair 2005). Another proposed explanation is that of internalized homophobia, or the internalization of negative expectations about being homosexual. Guilt, self-hatred, and self doubt may contribute to difficulty with a sexual relationship (Downey and Friedman 1995). Surveys of heterosexual couples have noted a similar decrease in sexual activity, but the time frame may be accelerated in lesbian couples (Lever 1995).

Lesbian couples may define "sexual activity" more broadly than do other couples to include activities like cuddling (James and Murphy, 1998). Lesbian sexual activities may reflect cultural biases of a particular historical moment. For example, at the height of the 1970s feminist movement, many lesbians rejected insertive sexual activities (such as fingers or dildos) that mimicked heterosexual intercourse. In recent years, if internet postings are any indication, lesbians appear to be embracing more diverse sexual practices including use of sex toys and lesbian-oriented pornographic literature.

For many lesbian couples, parenthood may become an issue. Lesbians with children from previous heterosexual relationships must help the children adjust to their new stepparent and family constellation. When the issue of bearing children themselves arises, lesbians can choose from a wide variety of options, which include at the most basic level, adoption and pregnancy. When pregnancy is chosen, they must decide which woman will carry the child, whose egg they will use, whether the father be a known or anonymous sperm donor; if known, what role the father may or may not have in the child's life, and so on. In some couples, these are all issues that have been thought out carefully; in others they may not. Couples unable to conceive a child together may experience a sense of loss (Crespi 1995). Depending on the state in which they live, lesbian couples also need legal advice on issues of power of attorney, custody, and second-parent adoption issues. (see Parenting subsection).

The Gay Male Couple

As with lesbian couples, gay male couples are both similar to and different from heterosexual couples. Greenan and Tunnell (2003) vividly describe the sociocultural developmental factors that can affect a growing gay boy's capacity for intimate relatedness and the kinds of difficulties he may have later as part of a couple. These challenges to intimacy often begin during the boy's childhood, precipitated by the awareness of homoerotic desire or with the emergence of gender discordant behavior, such a dislike of aggressive play or affinity for playing with dolls. Within the family, there is often a powerful admonition for the boy to keep his erotic feelings a deep and well-guarded secret. He learns that the expression of these persistent feelings will threaten much-needed affectionate ties to parents, friends, and siblings. The discovery of erotic feelings is traumatic for the gay boy in ways that it is not for straight boys who are allowed to speak of and explore their heterosexual desires. The young boy is left on his own with a secret that cannot be shared, and this can lead to the defensive self-reliance and isolation that affects the ability to experience intimacy in adulthood.

McWhirter and Mattison (1984) interviewed 156 gay male couples who had been together anywhere from 2 to 37 years. They conducted both structured and semi-structured (open ended questions) interviews and organized their findings by describing six stages of development for gay male couples:

- Blending (First year)

- Nesting (Years 2-3)

- Maintaining (Years 4-5)

- Building (Years 6-10)

- Releasing (Years 11-20)

- Renewing (Beyond 20 Years)

McWhirter's and Mattison's analysis normalizes gay male relationship development by emphasizing its similarities to that of heterosexual couples. Subsequent studies often discuss the differences between gay male couples and heterosexual couples. Today, gay male couples face choices on many issues, including: monogamy vs. the negotiation of non-monogamy, the question of raising a family, the dynamic around HIV and the negotiation of non-traditional gender roles. There are gay male couples who have sex outside their primary relationships. Other couples practice monogamy. Surrogacy and adoption have allowed gay male couples to raise children, thus creating a new model for a family and questioning traditional concepts of family and family values. The current debate over gay marriage is only one aspect of the emergence of gay relationships into the public awareness, challenging silence and stigmatization.

Clinical Example

Some common issues emerged in the course of treating a couple that was deciding whether to remain together or part ways. Andrew, the younger of the two men, had many previous short-term relationships. Brian, the oldest son of a young single mother, had only one previous relationship, but it was long-term and ended when his partner died of cancer.

Andrew, although committed to Brian, wanted sexual exploration outside the relationship. Brian accepted this, but with some trepidation. Andrew wanted Brian to be less fearful and join him in sexual exploration outside the relationship. Andrew, feeling that Brian was only interested in the appearance of a closed, monogamous relationship, dreaded being trapped in a situation like his parents' relationship, one defined entirely by social convention.

The exuberance of sexual variety helped Andrew feel masculine and sexy. Brian felt hurt that his monogamous love was experienced as feminizing or stifling. He was aware of Andrew's dependence on him for security and safety. Brian, on the other hand, lacked a father figure in childhood, and had taken on a paternal role for his younger siblings. He readily took on this role with Andrew and experienced his own wish to be cared for as very secret and shameful. In fact, Andrew enacted some of Brian's worst fears related to his own absent father: difficulty with commitment and faithfulness and abandonment by a man he loved.

The therapy for this couple focused on the elucidation of these previously unconscious patterns, and the working through of the transferences to each other. With this, they were better able to understand their relationship and the needs each brought to it.

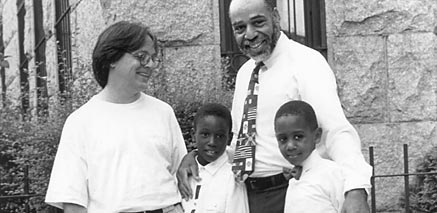

Parenting

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people have always had children. In the past this usually occurred in the context of a heterosexual marriage or relationship. In more recent decades, same sex couples have been creating their own families through reproductive technologies and adoption. Some gay couples have also created new family constellations by co-parenting children with another person (perhaps the biological father or mother) or couple.

Some examples:

Liz and Sharon are foster and adoptive parents through their local Social Services Department. Ten years ago when they started investigating this option, they were told they could not provide a foster home as an openly gay couple. They decided that Liz would go through the training and certification as a "single" parent, listing Sharon as a "roommate" living in the home. After the first two years and a couple of successful child placements in their home, the Department asked Sharon to go through the certification process as well, and they are now registered as a couple. They have two children they adopted after their placement, and they currently have one foster child who is in the process of going back to her birth mother.

Edward had two children with Martha while he was married in the 1960's. After he came out as a gay man and divorced Martha, they continued to be friends and shared custody and parenting responsibilities for their son and daughter. Today the son and daughter are grown and have children of their own. Edward and his partner Greg frequently have some or all of their five grandchildren stay over at their home during school vacations and holidays.

Janet and Lourdes have two school-aged sons. Each was conceived through insemination with an anonymous donor. Janet was the birth mother for the older son, and Lourdes gave birth to the second child.

Marvin, Carl, and Leah were college friends. Marvin and Carl eventually became a couple, and Leah came out as a lesbian. The couple asked Leah to co-parent a child with them. Using Carl as the inseminating donor, Leah got pregnant and gave birth a daughter. The friends live near each other, and have written agreements about custody, school, holidays, and how to resolve any disagreements about parenting that might arise. Although it can sometimes get complicated, the three friends find raising their first child together to be rewarding and find that they value each other's help in caring for their daughter. They are in the process of planning to have another child, this time with Marvin as the biological father.

Studies show that children raised by two mothers or two fathers have no more psychological problems than children raised in other types of households (Stacey & Biblarz 2001, Perrin et al. 2002). They do seem to be more open and tolerant of sexual diversity, an attribute which could be considered a strength. At least one study has suggested that lesbian parents may be more likely to raise girls who later identify as lesbian or bisexual, but other studies have not had that finding.

Same sex parents face many of the same challenges as heterosexual parents, but there are some unique issues. Where one parent is the biological parent of the child or children, there can sometimes be tension if the biological parent uses her or his status to exert power in the relationship, or if the second parent feels diminished in status. Same sex parents solve the issues of what the children will call them in different ways, with some using "mommy and mama" or "daddy and papa," others using names for mom or dad that reflect their heritage or ethnicity, and others having their children call them by their first names. The issues of coming out to one's kids is more pertinent for parents who first raised children in the context of a heterosexual relationship, since children raised by a same sex couple from the beginning are generally aware of their parents' relationship. Same sex couples may find that they have to come out to pediatricians, teachers, day care providers, and others who have contact with their children so that they can both share decision-making and childcare responsibilities.

Same sex parents often face legal discrimination in trying to have and raise children. In some states, gay people are banned from adopting children altogether. In other states, gay couples are able to adopt as a couple, but not being able to marry denies their children protections that being a married couple would afford. The spouse who leaves a heterosexual marriage after coming out as gay can face similar discrimination in decisions about custody and visitation of children from that marriage. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychiatric Association have issued position statements supporting adoption and co-parenting by same sex couples, recognizing that legal support for these families leads to healthier families and children.

Having children can be fulfilling, exhausting, and rewarding for same sex parents just as for heterosexual parents. It can also feel alienating to the couple, who may not have gay friends with children and who may not easily be able to participate in activities in the gay community once they have kids. They may similarly feel isolated at times in the typical parent circles as the only same-sex couple. Finding supports can be important both for the parents and kids.

Resources

deHaan L., Nijland S. 2004. King and King and Family. Tricycle Press.

Parnell P, Richardson J. 2005. And Tango Makes Three. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Martin, A. 1993. The Lesbian and Gay Parenting Handbook: Creating and Raising our Families. New York: Perennial.

COLAGE - Children of lesbians and gays everywhere. Sponsors Family Week in Provincetown and other events.

(L-R) Filmmaker Lucy Winer and

Golden Threads founder Christine Burton

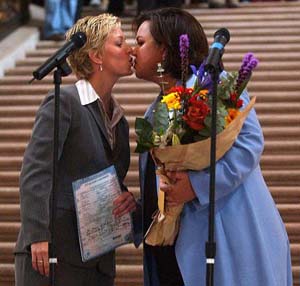

Lesbian activists Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin

marry in San Francisco Valentine's Day 2004.

Aging

Different generations of LGBT people may have very different experiences related to their sexual and gender identity. For example, a lesbian who went through her adolescence in the 1950s would have come of age in an era in which openness about sexual orientation would have been almost unthinkable. Those 85 or older, grew up in a time when openness about sex, much less sexual orientation, was extremely limited. Certain age cohorts may have experienced (or participated in) gay civil rights efforts in their young adult development. For many gay men (and often their lesbian friends as well), HIV and AIDS were a critical part of their early and middle adulthood. This illness had far-reaching consequences as they aged because of experiences of multiple losses, and possibly greater subsequent isolation.

As we age, all people face the tasks of finding meaning and accomplishment in work and relationships, making decisions about retirement, and approaching new phases of life with a continued sense of meaning, purpose, and integrity. There are special issues to consider for LGBT people who are dealing with these developmental tasks of aging. For instance, many older LGBT individuals have children (often from prior heterosexual marriages), but many others do not. For those with children, as with their heterosexual counterparts, children and grandchildren can be an important source of satisfaction and support, in addition to providing a sense of generational continuity. However, for some, their LGBT identity may make it more difficult to have satisfying, close relationships with their children and grandchildren. Some evidence suggests that older lesbians are more likely than older gay men to have children, and if they have children, lesbians are more likely to have stronger connections with them than older gay men have with their children.

Clinicians, erroneously assuming that older people are no longer

sexual, may avoid sexual history questions. This avoidance in

older LGBT individuals may leave significant gaps in the clinician's

knowledge of the patient's life. Although problems with sexual

functioning may emerge related to age in GLBT individuals, most (as most

heterosexual seniors) continue to have sexual desire and activity. For

lesbians, greater sexual satisfaction may occur at older ages related

to decreased shame about sexual orientation and increased comfort with

body image. Some older gay men may express concerns about

diminished sexual functioning such as sexual stamina, arousal, and

ability to reach orgasm. Their concerns may be heightened by the

experience of finding themselves less sexual desirable, especially if

the older gay man's connection with the gay community has mostly been

in sexualized venues such as cruising areas or gay pick-up bars.

It is important to address and assess isolation in LGBT seniors because

it may have significant effects on physical and mental health. Same-sex couples with a few exceptions do not have legal protections that

accrue to married heterosexuals. The lack of legal protections

for gay and lesbian couples means that illness and death of one's partner in later

life can have serious, adverse repercussions in matters of inheritance,

health insurance, pensions, and health care decision making. In

some cases, this can lead to loss of contact with a partner if the

partner's biological family so decides or if couples feel uncomfortable

revealing their connection to the partner's family. Recently, organizations for older gay and lesbian people have arisen

in larger cities such as New York and San Francisco, including SAGE

(Services and Advocacy for Gay Elders, www.sage.org

), but resources are limited in other areas of the U.S.

Although many smaller cities and regions now have LGBTQ centers, services

for older people may not be available or a priority, and older people

may not be aware of them or feel comfortable using them. Some retirement communities and assisted living facilities have been

developed for LGBT populations, and more are planned, but these are only

likely to be available for LGBT people with adequate financial

resources. Gay and lesbian retirees, like heterosexual retirees,

may be leaving the work force at earlier ages and in relatively better

health than prior generations, and may continue to be active and desire

a retirement community that is at least LGBT sensitive long before they

require assisted living or a skilled nursing facility. For now,

most LGBT people needing residential support may be faced with moving

into a facility without special support for LGBT issues. They may

feel forced to consider going back into the closet if they have

developed a gay life within their existing community, but do not feel

comfortable coming out again to a new set of strangers. Berger RM, Kelly, JJ. 1996. Gay men and lesbians grow older. In Textbook

of Homosexuality and Mental Health, ed. Cabaj RP, Stein TS.

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Berzon, B. 1988. Permanent Partners: Building Gay and

Lesbian Relationships That Last. New York: Dutton. Cohler BJ, Galatzer-Levy RM. 2000. The Course of Gay and

Lesbian Lives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. D'Ercole, A. & Drescher, J., eds. 2004. Uncoupling

Convention: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Same-Sex Couples and

Families. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press. Glazer, D.F. & Drescher, J., eds. 2001. Gay and Lesbian

Parenting. New York: The Haworth Press. Green, J. 1999. The Velveteen Father: An Unexpected

Journey to Parenthood. New York: Villard. Mamo, L. 2007. Queering Reproduction: Achieving

Pregnancy in the Age of Technoscience. Durham: Duke

University Press. Further reading

Post-Test

References